Liability to UK tax is broadly determined by the application of the concepts of “domicile” and “residence”.

Domicile

UK law relating to domicile is complex and differs from the laws of most other countries. Domicile is distinct from the concepts of nationality or residence. In essence, you are domiciled in the country where you consider you belong and where your real and permanent home is.

When you come to live in the UK you will not generally become UK domiciled if you intend, at some point in the future, to leave the UK.

Residence

The UK introduced a statutory residence test in 6 April 2013. Residence in the UK normally affects a whole tax year (6 April – 5 April the following year) although in certain circumstances “split year” treatment may apply.

For more details on residence please read our separate UK Resident/Non-Resident Test information note.

Remittance Basis

An individual who is resident but not domiciled in the UK can choose to have his or her non-UK income and gains taxed in the UK only to the extent that they are brought into or enjoyed in the UK. These are called ‘remitted’ income and gains. Income and gains made abroad, which are left abroad, are called ‘unremitted’ income and gains. Major reforms regarding how non-UK domiciliaries (“non-doms”) are taxed were implemented in April 2017. Additional advice should be requested.

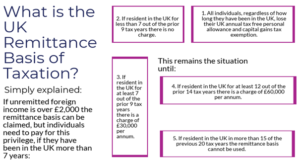

The rules are complex but in summary, the remittance basis will generally apply in the following circumstances:

- If unremitted foreign income is less than £2,000 at the end of the tax year. The remittance basis automatically applies without a formal claim and there is no tax cost to the individual. UK tax will be due only on foreign income remitted to the UK.

- If unremitted foreign income is over £2,000 then the remittance basis can still be claimed, but at a cost:

- Individuals who have been resident in the UK for at least 7 out of the prior 9 tax years must pay a Remittance Basis Charge of £30,000 in order to use the remittance basis.

- Individuals who have been resident in the UK for at least 12 out of the prior 14 tax years must pay a Remittance Basis Charge of £60,000 in order to use the remittance basis.

- Anyone who has been resident in the UK in more than 15 of the previous 20 tax years, will not be able to enjoy the remittance basis and will therefore be taxed in the UK on a worldwide basis for income and capital gains tax purposes.

In all cases (except where unremitted income is less than £2,000) the individual will lose the use of his or her UK tax-free personal allowances and capital gains tax exemption.

Income Tax

For the current tax year the UK top rate of income tax is 45% on taxable income of £150,000 or more. Married persons (or those in a civil partnership) are taxed independently on their individual incomes.

As detailed above, if you are resident, but not domiciled, in the UK and choose to be taxed on the “remittance basis” you are taxable in the UK only on income that either arises in, or is brought to, the UK in any tax year.

Individuals resident and domiciled in the UK, or those who do not use the remittance basis, pay tax on all income worldwide on an arising basis.

Careful planning prior to arriving in the UK is needed to avoid unintentional remittances. In each case, attention must be paid to any relevant double taxation treaty.

Any remittances to the UK of income (or gains) used to make a commercial investment in a UK business are exempt from an income tax charge.

Capital Gains Tax

The UK rate of capital gains tax ranges from 10% to 28% depending on the nature of the asset and the income level of the individual. Married persons (or those in a civil partnership) are taxed separately.

As above if you are resident, but not domiciled in, the UK and choose to be taxed on the “remittance basis” you are liable to capital gains tax on gains made from the disposal of assets situated in the UK or from those which are outside the UK if you remit the proceeds to the UK. Non-sterling currency is treated as an asset for capital gains tax purposes and therefore any currency gain (measured against sterling) is potentially chargeable.

As with income, gains realised by certain offshore structures can be attributed to a UK resident individual under complex anti-avoidance rules; for example, gains realised by “closely controlled” non-UK companies (broadly companies under the control of five or fewer “participators”) are attributed to the participators individually.

Gains on the disposal of certain types of asset, such as a main residence, UK government securities, cars, life assurance policies, savings certificates and premium bonds may be relieved from capital gains tax.

Inheritance Tax

Inheritance tax (IHT) is a tax on an individual’s wealth on death and may also be payable on gifts made during an individual’s lifetime. The UK inheritance rate is 40% with a tax free threshold of £325,000 for the tax year 2019/2020.

Liability to inheritance tax depends on your domicile. If you are domiciled in the UK you are taxable on a worldwide basis.

A person who is not domiciled in the UK is taxable only on the transfer of assets situated in the UK (including transfers to successors/beneficiaries that occur on death). For inheritance tax purposes only, special rules apply. Any person who has been resident in the UK (for income tax purposes) for more than 15 years out of a continuous period of 20 years will be treated as being domiciled in the UK for IHT. This is called “deemed domicile”.

Certain lifetime gifts are exempt from inheritance tax provided the donor survives seven years and divests himself of any benefit. Strict rules have been introduced in cases where the donor retains or reserves a benefit out of the gift (e.g. gives away his house but continues to live in it). The effect of these changes will be to treat the donor for IHT purposes, in most cases, as if he had never made the gift.

Transfers of property between spouses of the same domicile status are exempt from inheritance tax, as are transfers by a spouse with a non-UK domicile to a UK domiciled spouse. However the amount that can be transferred by a UK domiciled spouse to a non-UK domiciled spouse without incurring an inheritance tax charge is limited to £325,000. It is, however, possible for a non-domiciled spouse to elect to be treated as domiciled, which would enable the full spouse exemption to be claimed. Once such a deemed domicile had been claimed the spouse would remain deemed domiciled until a number of years of non-residence had subsequently been re-established.

The UK remittance regime is a particularly attractive example and although the rules have changed since 2008, with the latest changes being implemented in April 2017, this regime remains of significant benefit to HNW non-doms living in the UK. In fact, the advantages for individuals living in the UK for less than 7 years remain very generous (please see below).

The UK remittance regime is a particularly attractive example and although the rules have changed since 2008, with the latest changes being implemented in April 2017, this regime remains of significant benefit to HNW non-doms living in the UK. In fact, the advantages for individuals living in the UK for less than 7 years remain very generous (please see below).